This work was done in collaboration with my research advisor, Dr. Sam Calisch, in the Center for Bits and Atoms (under the direction of Professor Neil Gershenfeld) at MIT.

After working at the CBA for some time previously on MEMS actuators, I was drawn to research in which the structure of materials itself could be exploited to create metamaterials with target material properties. My next research supervisor, Dr. Sam Calisch,was developing manufacturing techniques to convert 2D sheet materials into 3D metamaterials. Specifically, he was using origami and kirigami techniques to convert sheet materials like copper and carbon fiber into metamaterial structures which gained strength and energy absorptive properties due to the geometry of the folds rather than the properties of the materials themselves. These techniques were still grounded in sustainability principles – such structures could be unfolded and refolded into other bulk materials and transportation and disposal could be streamlined, reducing carbon emissions – but appealed to another growing interest in my academic journey which was the incredibly significant and almost shocking role structure and geometry from the atomic scale to the macro scale played in resultant material and bulk material properties. The materials science classes I was taking in quantum mechanics, electronic, optical, magnetic and mechanical properties of materials re-confirmed this over and over as bulk material properties were broken down to the very structure and location of atoms or slabs of materials in relation to each other and how forces in these geometries led to useful material properties that could even be manipulated.

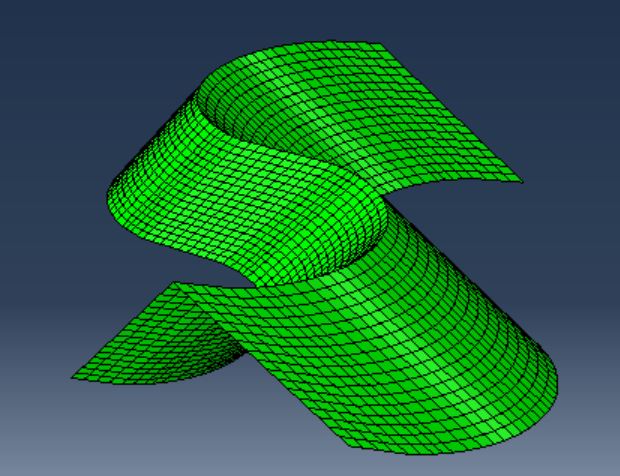

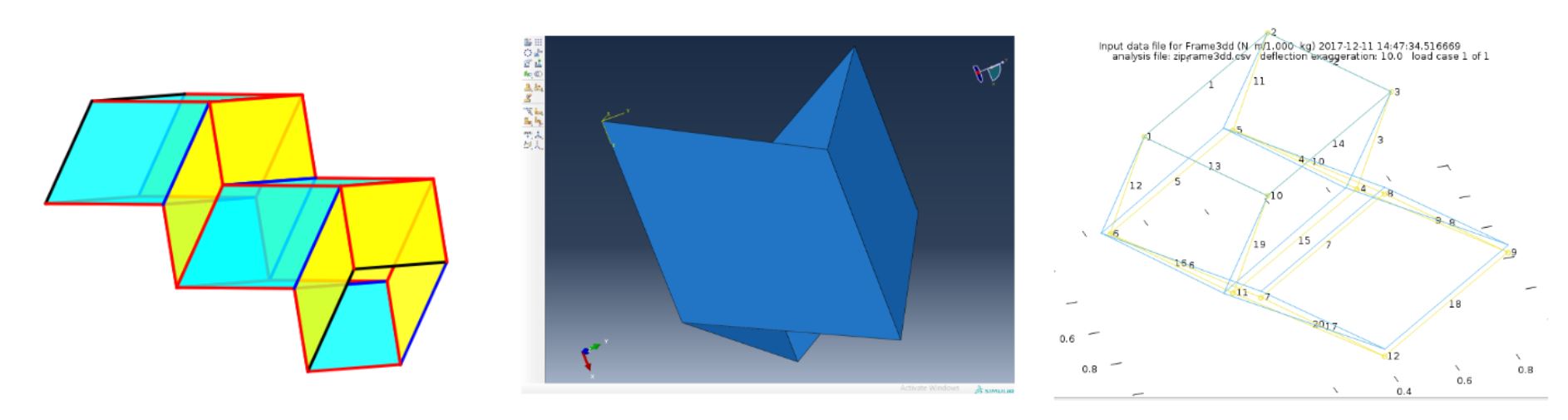

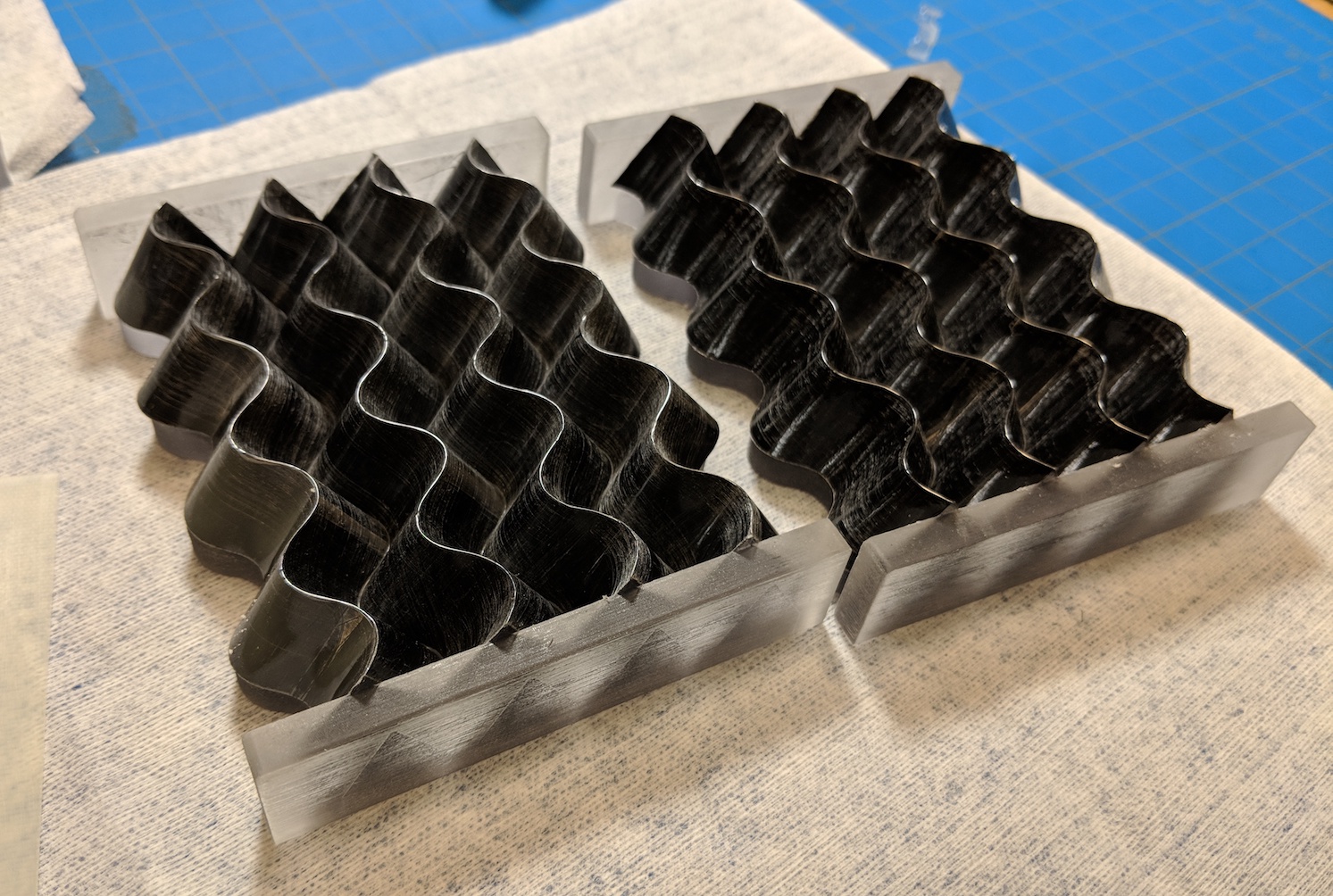

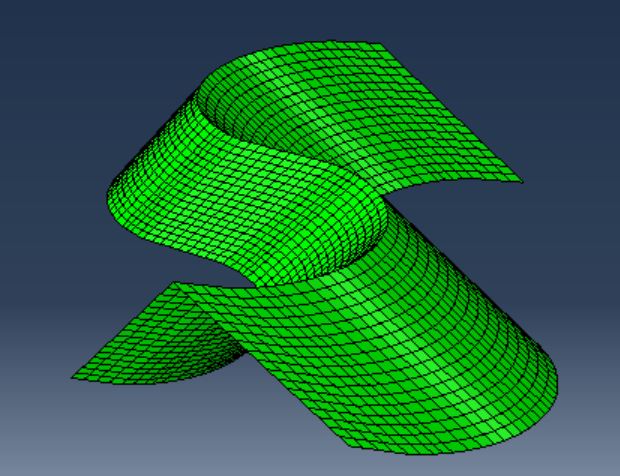

Pursuing this interest, I switched into working on a research project with Sam funded by the Toyota Motor Corporation to design folded cellular materials that could replace honeycomb sandwich panels used in vehicles’ energy-absorbing crash panels. These folded structures were more property-tuneable and efficient to manufacture compared to existing honeycomb panels. Theoretical work had shown (Gattas and You, 2015) that folded cellular materials (particularly those with curved creases based on the Miura-Ori fold) can greatly exceed the performance of honeycombs, but experimental validation only showed modest improvement, mostly due to inadequate manufacturing methods. Sam had already developed novel manufacturing methods to increase fold precision and efficiency but there were many parameters to tune within the fold structure: material thickness, radii of curvature, and fold angle amongst others. We decided to use simulation techniques to streamline the process of design and only manufacture designs that simulation showed to be robust in expected crash situations. To start with, I used a python framework for Frame3dd, a structural analysis software, to implement a bar and hinge model that had been proposed to analyze origami structures (Filipov, 2017). Given a geometric input, I used Frame3dd to calculate and visualize stresses, strains, and modal deformations of the folded structure. To streamline the analysis I started from a general file that describes the geometry of the kirigami structure. For this purpose, I used Erik Demaine’s FOLD (Flexible Origami List Data structure) file framework which describes origami models by storing a mesh with vertices, edges, faces, and links between them (Erik D. Demaine, 2016). My python script took three items as input: 1) a FOLD file with additional arguments for forces and constraints to apply, 2) arguments describing the material properties of folded sheet, and 3) an argument for the bar and hinge model type. Using these parameters, the script was able to simulate the structural response of the folded sheet. Developing this python script involved deconstructing the geometry from the FOLD file into arguments that Frame3dd could understand and also deconstructing the faces of structures using different bar and hinge models (i.e. 4 nodes-5 bars, 4 nodes-6 bars, 5 nodes-8 bars).

(left to right): zippertube from FOLD file in Demaine’s Fold Viewer; zippertube created in Abaqus; analysis results of zippertube from Frame3dd

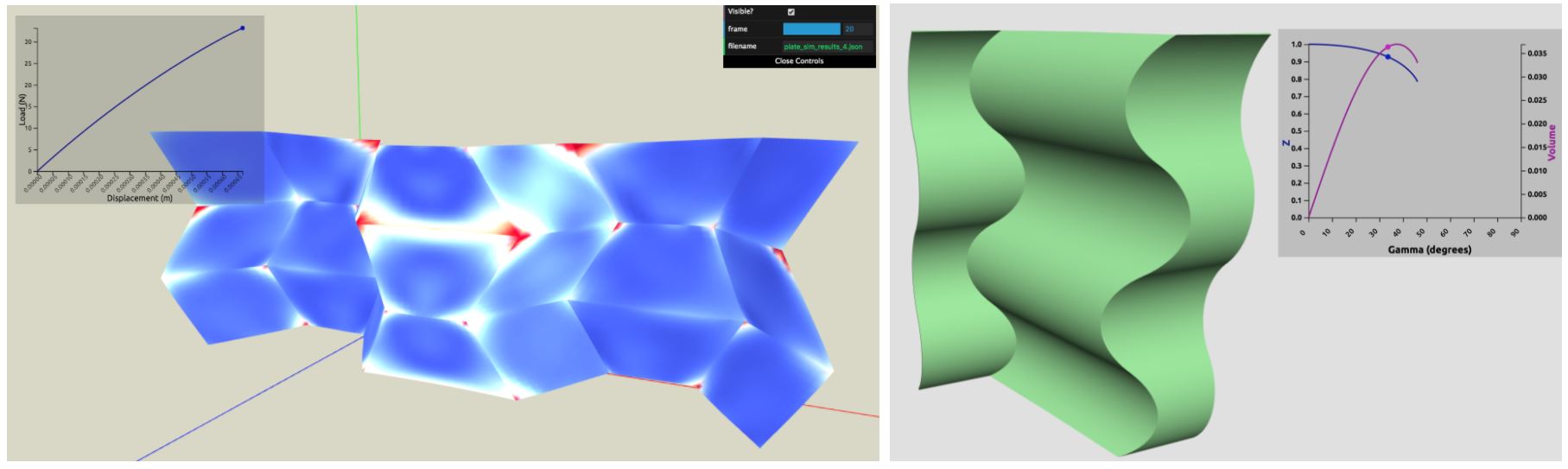

(left to right): Screenshot from Hermite element simulation; curved crease kirigami structure from Hermite patch simulator (from Sam Calisch's Hermite patch simulator)

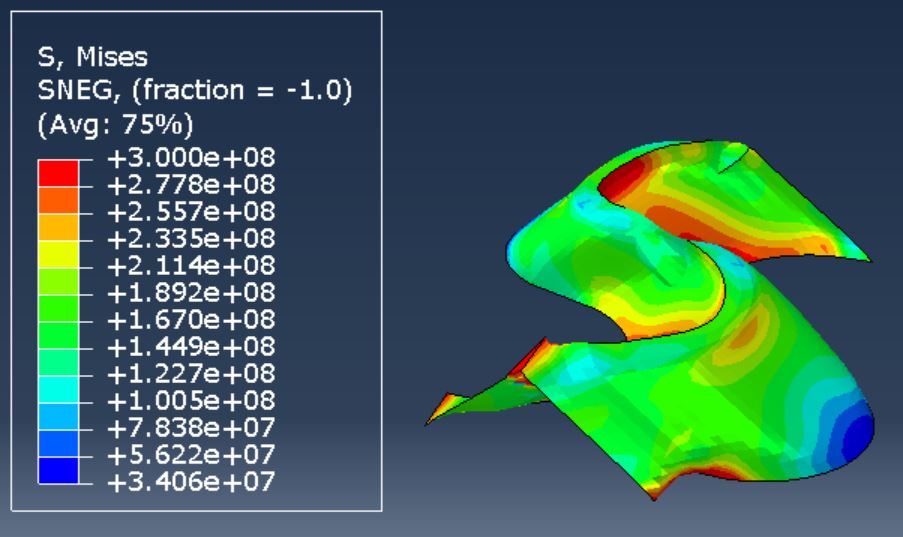

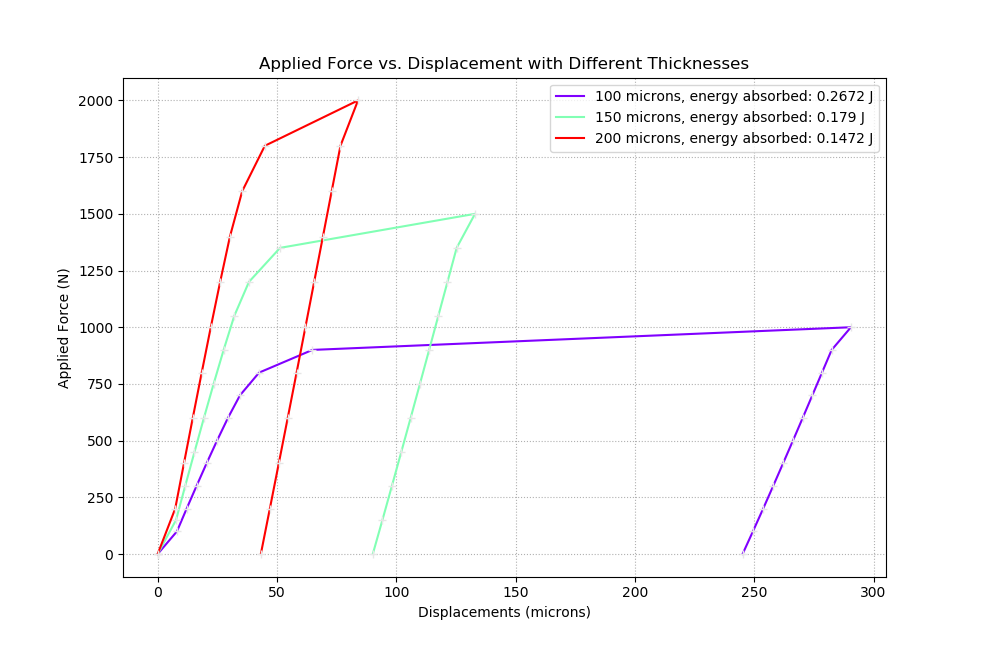

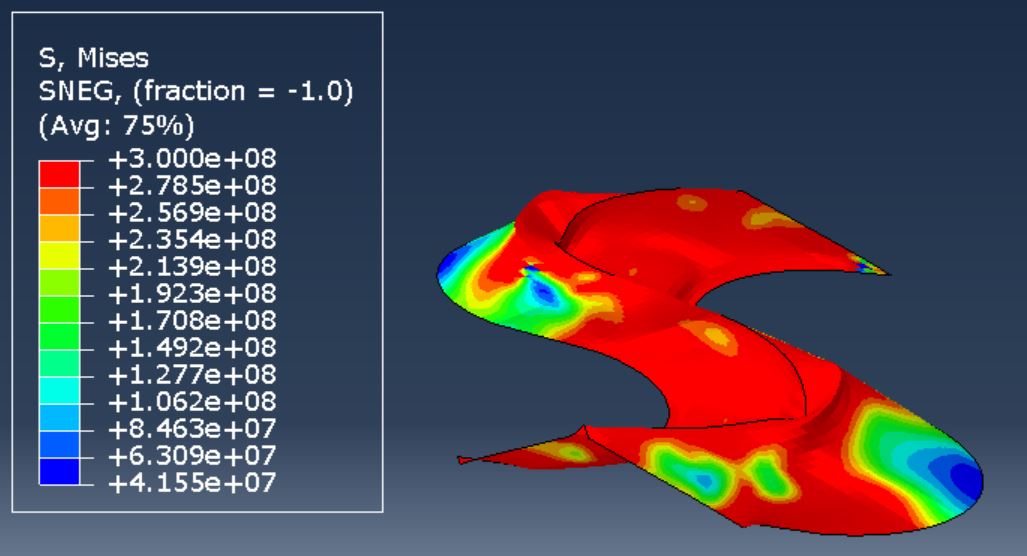

While this approach worked for structures like the zipper tube or the Tachi Miura polyhedron, it was less reliable for the curved crease structures we were interested in. For this purpose, we switched to using Abaqus, again a tool that neither I nor my advisor had experience with. Through many cycles of iteration and working through Abaqus’ Python API documentation, I developed a python pipeline for constructing kirigami geometries in Abaqus, applying boundary conditions, contact properties, meshing, applying loads and finally simulating the energy absorption potential of curved crease Miura-Ori folds with varying parameters. I was able to visualize applied force vs displacement for different material thicknesses, different radii of curvature, and different fold angles. This pipeline streamlined simulation for the particular property of energy absorption and was maintained as group documentation for how to use Abaqus for simulating complex geometries like kirigami folds.

(left to right) Physical model of curved crease model created by Sam; bottom view of model crushed in experiment taken by Sam; one unit of curved crease model undeformed in Abaqus simulation UI; one unit of curved crease model crushed in simulation.

(left to right) Applied force in Newtons vs. Displacement in microns over different thicknesses; Deformed 100 micron thick model in simulation after 10 steps of applying force.

Detailed documentation of how to run an Abaqus simulation for this specific use case can be found here